The famous “jinx” of the Presidents' Trophy is back.

Since 2013, no team that has finished the season ranked first in the NHL has won the Stanley Cup in the same season, a fact that became a reality with the Rangers' elimination last Saturday.

I read this week that this is “proof” that the regular season means nothing when it comes to the playoffs.

I think – and hope – it's generally accepted that the team that wins the Presidents' Trophy isn't “supposed” to win the Stanley Cup, and that we're not talking about bad luck, but statistical reality.

After all, first place has come down to 3 points or less 6 times in the last 10 years, and 5 of the last 10 Stanley Cup winners have been in the top-5 overall. Having success during the season helps, and the story could have been very different if a few games #82 of a season had ended differently.

The first-place team should, however, logically have a better chance than a team that finished 16th. No?

The divisional system seems broken

The NHL celebrated (the word is strong) the tenth anniversary of its new playoff format, in 2023.

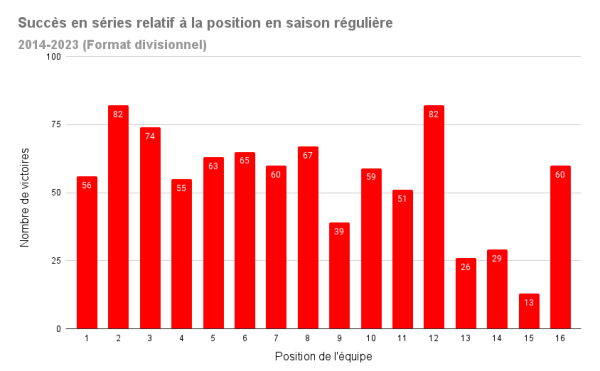

The balance sheet after 10 years gives very little weight to a team's playoff position.

Hold on to your hats: the jinx is real and the numbers don't lie.

Since 2014, the 10 teams that finished 1st have fewer wins (56) than the 10 teams that finished 16th (60 ).

Please reread this sentence to grasp the magnitude of the situation.

In fact, the 1st-placed teams are tenth (!) out of sixteen in terms of wins.

The order is as follows: 2, 12, 3, 8, 6, 5, 7, 16, 10, 1, 4, 11, 9, 14, 13, 15.

Don't try to understand. The graph expresses that the trend is that there is no trend.

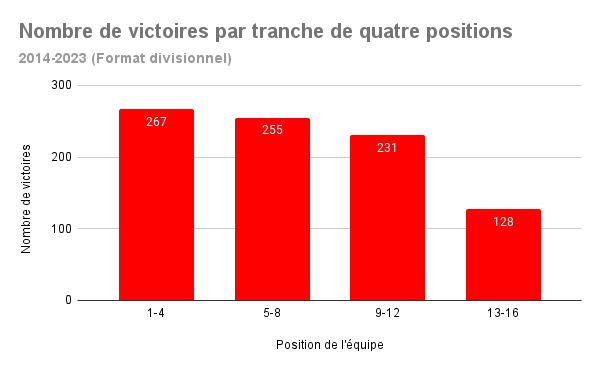

On average, a team that finishes the season among the top 4 teams in the league wins 6.675 games in a playoff run, while a team between ninth and twelfth wins 5.755 games. The additional value of a first-place finish is not enormous.

In short, it could be said that the importance of the playoffs is currently much higher than that of the regular season.

Was it better before?

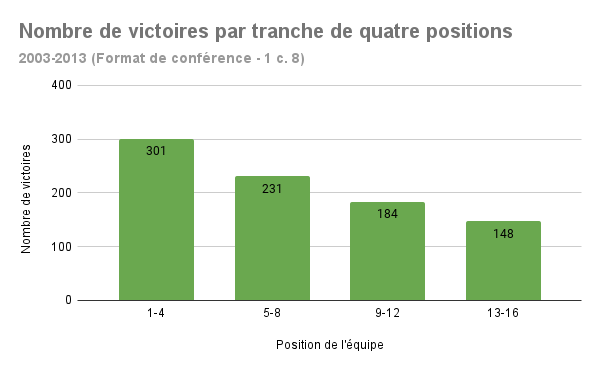

What was it like before the playoff format was changed? Here's a chart that makes a little more sense.

Apart from the small anomalies that are normal in the exercise of an inexact science, the slope is relatively proportional and, above all, downward-sloping. A higher position normally translates into more successes than a lower position.

A team finishing in the top-4 would end the series with an average of 7.525 wins, compared with 5.755 for teams 5 to 8 and 4.6 for teams 9 to 12.

In short, you could say that the importance of the regular season was higher before 2014.

And since the playoffs can't be “unimportant” in a context of 4-of-7 playoff eliminations, the conclusion is that they were “more predictable”, but not necessarily so, if you know what I mean.

But why?

To define the problem even better, it's absolutely necessary to forget the 1 to 16 and dig into positions 1 to 3 of each division.

Excluding the abnormal pandemic series, we can see that under the new format, the second-place team is slightly more successful than the first-place team, which has barely more wins than the third-place club.

What explains these figures?

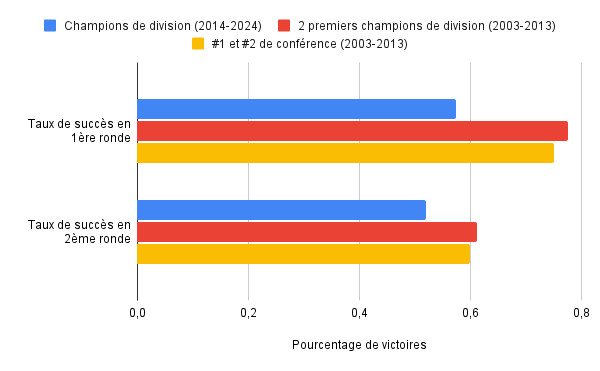

Since 2013, 23 out of 40 division champions have advanced to the second round, a first-round success rate of just 57.5%.

12 of these 23 division champions have won the second round against the #2 or #3 team, a success rate of just over 52%.

It's hard to compare with the old format, given that there were three divisions per conference. Let's do the exercise with teams #1 and #2, who were also sent to the first round against teams #7 and #8.

The top two teams in each conference advanced 31 out of 40 (77.5%) to the second round, and 19 of them (61.2%) to the conference final. This represents an increase of 20% in the first round and 9.2% in the second round.

.

This table gives us a few clues.

First, nothing has changed in terms of first-round match-ups. The drop in the first-round success of the league's top teams suggests two possibilities: that entering the playoffs on cruise control is simply not ideal, and/or that the teams finishing at the bottom of the standings are more competitive than they were.

It should also be noted that, prior to the format change, the table followed the principle of automatic reseeding , i.e. in the event of a first-round upset, the higher-ranked team would get the “advantage” of playing the surprise team.

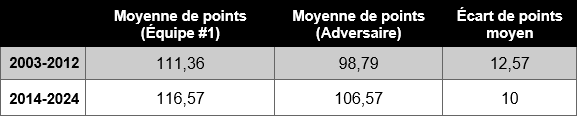

Since the change, the average gap between a conference champion and its second-round opponent has narrowed, but not by much. However, the opponent's point average has soared.

Note also that the Bruins' historic 135-point season inflates the figures.

Five times in the last 10 years, a conference champion has faced a team in the second round by a margin of 3 points or less. In the previous 10 years, this happened only once.

Nonsense

The duels between the #1 vs. #2 teams in the same division in the second round make even more sense when you consider that it has happened six times in the last ten seasons that the two best teams in the East were in the same division… and that this has been the case every season since 2016 in the West!

Under the new format, clashes between the #1 and #2 teams in the same conference are not only possible, but very often normalized and expected. It's happened twice… this year!

And we're not talking about #1 vs #3, which was also impossible pre-lockout.

Such a duel this early in the playoffs used to be unthinkable, although clashes between #2 and #3 were indeed possible as early as the second round.

Problems before

Of course, in such a situation, the issues were different, and almost as serious. Clashes between #2 and #3 were often not as bad, as one of the three division champions was often weaker… But also illogical, as a #1 could face a #4, #5 or even #6 who had finished the season with more points than the #3 team.

In 2012, for example, the Panthers finished 6th in the East, but entered the playoffs with the #3 tag.

The Penguins and Flyers (#2 and #3) faced off in the first round.

That was one problem, but the League has created another with the current format. Perhaps the solution lies somewhere in the middle, in a world where the format doesn't care about divisions and where teams simply play each other according to their ranking: 1 v. 8, 2 v. 7, 3 v. 6, 4 v. 5.

However, we know that the NHL wants to fuel its rivalries.

The devil's advocate would say that these can still be created in a conference format, and would give as an example the many Penguins-Flyers and Penguins-Capitals duels of the 2010s, and the Canadiens-Senators, Canadiens-Bruins and Canadiens-Sénateurs series. I don't know the devil's advocate, but I imagine he'd also make the case that it's not unhealthy to create rivalries between the best teams in a conference, plain and simple. He might even say that the wild-card concept we love so much can prevent some interesting intra-divisional clashes.

It all depends on what you want

You know when Marc Bergevin used to tell us that “once you're in the playoffs, anything can happen”?

Well, that's been true to some extent since 2013, and there are plenty of examples.

One thing seems clear: both models have been successful at what they set out to do… up to a point.

The question now is, what do we want, and more importantly, what does the NHL want to achieve? Do we want the playoffs to be more unpredictable, at the expense of the 82 games that have gone before? Do we want to offer a “logical” chance that respects the order of success in the regular season, even if it means being more predictable?

There will always be surprises, whatever the format. Remember that the Canadiens (8) took out the Capitals (1) and the Penguins (4) en route to being surprised by the Flyers (7), who in turn took out the Devils (2).

And the best teams eventually emerge, as when you consider that every other time, one of the top two clubs in a conference lifts the Stanley Cup.

Considering this, does it make “sense” to offer extra, fair value to a team that has done well in the previous eighty-two games?

I think these are questions that need to be asked.